What I find most interesting is Kurokawa’s statement, “Nature is disorder. I like to use nature to create order… I like to denature.” I have always thought of nature as a form of order — ecosystems functioning in balance, patterns repeating, and life sustaining itself without human interference. In contrast, I tend to see human beings as the source of disruption and chaos. That is why his perspective feels so unexpected to me. By describing nature as disorder, he shifts the responsibility of structure and organization onto the artist. It suggests that order does not simply exist waiting to be admired; it can be constructed through interpretation and design

I was fascinated by his focus on synesthesia and the deconstruction of nature. He takes the natural randomness of our environment, such as the chaotic motion of microscopic particles, and translates it into highly controlled, digital audiovisual experiences. By acting as a “time designer,” Kurokawa ensures his pieces never just dissolve into a mess of noise. Instead, he carefully layers real-world field recordings with computer-generated graphics so that what you hear and what you see feels like a single, connected unit. This approach shows how we can use digital tools to completely rebuild our perception of the natural world.

Kurokawa’s style offers a great lesson on the importance of flow and artistic intention. When coding generative art, it is very easy for an algorithmic composition to lose its structure and overwhelm the audience. However, Kurokawa proves that by carefully guiding the transitions between order and disorder, an artist can successfully harness that chaos. His work is a powerful reminder that mastering the audio-visual flow is what transforms raw data and abstract code into a truly engaging and meaningful performance.

Kurokawa’s perspective on nature is grounded in a deep patience that I find interesting. He mentioned that nature doesn’t change overnight but evolves gradually, and he applies that same logic to his own work. He isn’t interested in the frantic race to keep up with every new tech development. Instead, he focuses on what he calls his “incremental evolution.” It makes his process feel much more intentional, like he is growing his art the same way a forest grows, rather than just chasing the next big update.

The author also mentioned Kurokawa’s two conceptual hangers, which are synaesthesia and the deconstruction of nature. Seeing his ATOM performance on YouTube really made those ideas click for me. It was not just a show. It felt like watching nature get dismantled and put back together in real time. The way the visuals fractured and then snapped back together in milliseconds felt exactly like the time design the writer described. It reinforced that idea of absolute instability, showing that nothing is actually solid and everything we see is just fragments in flux.

What I took away most was his wabi-sabi vibe. In a world where everyone is obsessed with the latest AI or new gadgets, he is just chilling and totally indifferent to the tools. He cares about the evolution of the work rather than the specs of the computer. It makes his cataclysmic walls of noise feel a lot more human. He is just a guy trying to find a bit of order in the chaos of the universe. He moves between the microscopic and the cosmic without ever losing his footing.

Reading about Ryoichi Kurokawa made me think differently about how scale and control work in audiovisual art. What stood out to me most was his idea of “de-naturing” nature, to uncover structures that are usually invisible. He breaks natural phenomena down into data, sound and image to create works that feel both precise and unstable at the same time, which makes the experience feel alive rather than fixed.

I was also drawn to how Kurokawa thinks about time. He sees his work as “time design” and he justify by constantly adjusting and reshaping it across performances and installations. His slow and evolving approach contrasts how quickly technology usually moves – he doesn’t seem interested in novelty for its own sake, but in letting ideas develop gradually, the way nature does.

Another aspect I found compelling is that Kurokawa doesn’t confine himself to a single platform or format. He moves fluidly between concerts, installations, sculptures and data-driven visuals, choosing the medium based on what the idea requires rather than forcing the work into one system. This flexibility reinforces his larger interest in scale and transformation, and it made me reflect on how artistic practice doesn’t have to be tied to one tool or discipline to remain coherent.

Hey there!

Here is the video of my 3rd Live Coding Demo combining audio and visuals from Hydra and TidalCycles.

I had some issues recording the audio.

Background: What is Pure Data?

Pure Data (Pd) is an open-source visual programming environment primarily used for real-time audio synthesis, signal processing, and interactive media. Programs in Pd are built by connecting graphical objects (known as patches) that pass messages and audio signals between one another. Unlike text-based programming languages, Pd emphasizes signal flow and real-time interaction, allowing users to modify systems while they are running.

Pd belongs to the family of visual patching languages derived from Max, originally developed by Miller Puckette at IRCAM. While Max/MSP later became a commercial platform, Pure Data remained open source and community-driven. This has led to its widespread use in experimental music, academic research, DIY electronics, and new musical interface (NIME) projects.

One of Pd’s major strengths is its portability. It can run not only on personal computers, but also on embedded systems such as Raspberry Pi, and even on mobile devices through frameworks like libpd. This makes Pd especially attractive for artists and researchers interested in standalone instruments, installations and hardware-based performances.

Personal Reflection

I find Pure Data to be a really engaging platform. It feels similar to Max/MSP, which I have worked with before, but with a simpler, more playful interface. The ability to freely arrange objects and even draw directly on the canvas makes the patch feel less rigid and more sketch-like, almost like thinking through sound visually.

Another aspect I really appreciate is Pd’s compatibility with microcontrollers and embedded systems. Since it can be deployed on devices like Raspberry Pi (haven’t tried it out though), it allows sound systems to exist independently from a laptop. This makes Pd especially suitable for experimental instruments and NIME-style projects.

Demo Overview: What This Patch Does

For my demo, I built a generative audio system that combines rhythmic sequencing, pitch selection, envelope shaping, and filtering. The patch produces evolving tones that are structured but not entirely predictable, demonstrating how Pd supports algorithmic and real-time sound design.

1. Timing and Control Logic

The backbone of the patch is the metro object, which acts as a clock. I use tempo $1 permin to define the speed in beats per minute, allowing the patch to behave musically rather than in raw milliseconds.

Each metro tick increments a counter using a combination of f and + 1. The counter is wrapped using the % 4 object, creating a repeating four-step cycle. This cycle is then routed through select 0 1 2 3, which triggers different events depending on the current step.

This structure functions like a step sequencer, where each step can activate different pitches or behaviors. It demonstrates how Pd handles discrete musical logic using message-rate objects rather than traditional code.

2. Pitch Selection and Control

For pitch generation, I use MIDI note numbers that are converted into frequencies using mtof. Each step in the sequence corresponds to a different MIDI value, allowing the patch to cycle through a small pitch set.

By separating pitch logic from synthesis, the patch becomes modular: changing the melodic structure only requires adjusting the number boxes feeding into mtof, without touching the rest of the system. This reflects Pd’s strength in modular thinking, where musical structure emerges from the routing of simple components.

3. Sound Synthesis and Shaping

The core sound source is osc~, which generates a sine wave based on the frequency received from mtof. To avoid abrupt changes and clicks, pitch transitions are smoothed using line~, which interpolates values over time.

I further shape the sound using:

expr~ $v1 * -1andcos~to transform the waveformlop~ 500as a low-pass filter to soften high frequenciesvcf~for resonant filtering driven by slowly changing control values

Amplitude is controlled using *~, allowing the signal to be shaped before being sent to dac~. This ensures the sound remains controlled and listenable, even as parameters change dynamically.

Randomness and Variation

To prevent the output from becoming too repetitive, I introduced controlled randomness using random. The random values are offset and scaled before being sent to the filter and envelope controls, creating subtle variations in timbre and movement over time.

This balance between structure (metro, counters, select) and unpredictability (random modulation) is central to generative music, and Pd makes this relationship very explicit through visual connections.

Conclusion

Overall, Pure Data feels less like a traditional programming environment and more like a living instrument, where composition, performance and system design happen simultaneously. This makes it especially relevant for experimental music, live performance and research-based creative practice.

(Somehow I can’t do recording with internal device audio… I’ll try recording it using my phone sometime)

What is Alda?

Alda is a text-based, open-source programming language designed for musicians to compose music in a text editor without needing complex graphical user interface (GUI) software.

The Alda music programming language was created by Dave Yarwood in 2012. Interestingly, he was a classically trained musician long before he was a competent programmer

Why Alda?

In contrast to working with complex GUI applications available at the time, Dave Yarwood found that programming pieces of music in a text editor is a pleasantly distraction-free experience.

How it Works

The process is beautifully simple:

- Write the notes in a text file using Alda’s syntax

- Run the file through the Alda interpreter

- Hear the music come to life

Key Features

Alda uses the General MIDI sound set — giving you access to over 100 instruments.

Basic Syntax

- Pitch: The letter represents the pitch.

cis C,dis D,eis E, and so on. - Duration: The number indicates how long it lasts in beats. In Alda, smaller numbers mean longer notes—it’s backwards from how we normally think!

- Octave: The octave number tells Alda how high or low to play.

c4is middle C,c5is one octave higher,c3is one octave lower.

Handy Shortcuts

>moves you up one octave<moves you down one octave

Chords and Rests

- The forward slash

/is your chord maker. It tells Alda to play notes at the exact same time. - Rests use

rinstead of a note name. The same duration rules apply.

Visual Aid

The vertical bar | does absolutely nothing to the sound. It’s just there to help you read the music more easily.

Demo

Here is the short demo I made using Alda!

It is a fairly simple Piano composition

Code

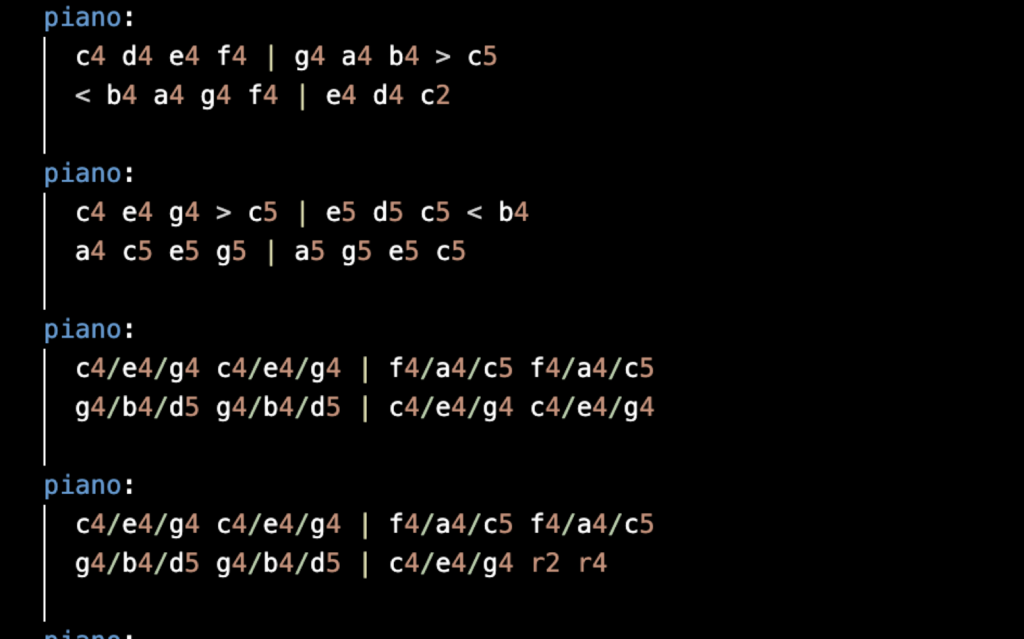

This is the code that I ran for the Demo Video !!

piano:

c4 d4 e4 f4 | g4 a4 b4 > c5

< b4 a4 g4 f4 | e4 d4 c2

piano:

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | e5 d5 c5 < b4

a4 c5 e5 g5 | a5 g5 e5 c5

piano:

c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 | f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5

g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 | c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4

piano:

c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 | f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5

g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 | c4/e4/g4 r2 r4

piano:

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | < b4 g4 e4 c4

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | < b4 g4 e4 c2 r2

piano:

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | e5 d5 c5 < b4

a4 c5 e5 g5 | a5 g5 e5 c5

piano:

c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 | f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5

g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 | c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4

piano:

c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 | f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5

g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 | c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4

piano:

c4 d4 e4 f4 | g4 a4 b4 > c5

< b4 a4 g4 f4 | e4 d4 c2

piano:

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | < b4 g4 e4 c4

c4 e4 g4 > c5 | < b4 g4 e4 c2 r2

piano:

c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 | f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5 f4/a4/c5

g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 g4/b4/d5 | c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 c4/e4/g4 r2 r2

piano:

c4/e4/g4 r2 | r1

piano:

c4 r2 | r1Alda represents a beautiful intersection between programming and musicianship—proof that sometimes the simplest tools can inspire the most creative work.

Thank You!!!