Overview + Breakdown

Max, also known as Max/MSP/Jitter, is a visual programming language for music and multimedia developed and maintained by software company Cycling ’74. Over its more than thirty-year history, it has been used by composers, performers, software designers, researchers, and artists to create recordings, performances, and installations. It offers a realtime multimedia programming environment where you build programs by connecting objects into a running graph, so time, signal flow, and interaction are visible in the structure of the patch. Miller Puckette began work on Max in 1985 to provide composers with a graphical interface for creating interactive computer music. Cycling ’74’s first Max release, in 1997, was derived partly from Puckette’s work on Pure Data. Called Max/MSP (“Max Signal Processing” or the initials Miller Smith Puckette), it remains the most notable of Max’s many extensions and incarnations: it made Max capable of manipulating real-time digital audio signals without dedicated DSP hardware. This meant that composers could now create their own complex synthesizers and effects processors using only a general-purpose computer like the Macintosh.

The basic language of Max is that of a data-flow system: Max programs (named patches) are made by arranging and connecting building-blocks of objects within a patcher, or visual canvas. These objects act as self-contained programs (in reality, they are dynamically linked libraries), each of which may receive input (through one or more visual inlets), generate output (through visual outlets), or both. Objects pass messages from their outlets to the inlets of connected objects. Max is typically learned through acquiring a vocabulary of objects and how they function within a patcher; for example, the metroobject functions as a simple metronome, and the random object generates random integers. Most objects are non-graphical, consisting only of an object’s name and several arguments-attributes (in essence class properties) typed into an object box. Other objects are graphical, including sliders, number boxes, dials, table editors, pull-down menus, buttons, and other objects for running the program interactively. Max/MSP/Jitter comes with about 600 of these objects as the standard package; extensions to the program can be written by third-party developers as Max patchers (e.g. by encapsulating some of the functionality of a patcher into a sub-program that is itself a Max patch), or as objects written in C, C++, Java, or JavaScript.

Max is a live performance environment whose real power comes from combining fast timing, real time audio processing, and easy connections to the outside world like MIDI, OSC, sensors, and hardware. Max is modular, with many routines implemented as shared libraries, and it includes an API that lets third party developers create new capabilities as external objects and packages. That extensibility is exactly what produced a large community: people can invent tools, share them, and build and remix each other’s work, so the software keeps expanding beyond what the core program ships with. In practice, Max can function as an instrument, an effects processor, a controller brain, an installation engine, or a full audiovisual system, and it is often described as a common language for interactive music performance software.

Cycling ’74 formalized video as a core part of Max when they released Jitter alongside Max 4 in 2003, adding real time video, OpenGL based graphics, and matrix style processing so artists could treat images like signals and build custom audiovisual effects. Later, Max4Live pushed this ecosystem into a much larger music community by embedding Max/MSP directly inside Ableton Live Suite, so producers could design their own instruments and effects, automate and modulate parameters, and even integrate hardware control, all while working inside a mainstream performance and production workflow.

Max/MSP and Max/Jitter helped normalize the idea that you can build and modify a performance instrument while it is running, not just “play” a finished instrument. This is the ethos of live coding – to “show us your screens” and treat computers and programs as mutable instruments.

Live Coding + Cultural Context

With the increased integration of laptop computers into live music performance (in electronic music and elsewhere), Max/MSP and Max/Jitter received attention as a development environment available to those serious about laptop music/video performance. Max is now commonly used for real-time audio and video synthesis and processing, whether that means customizing MIDI controls, creating new synths or sampler devices (especially with Max4Live), or just creating entire generative performances within Max/MSP itself. Live reports and interviews repeatedly framed their shows and laptops running Max MSP, which helped cement the idea that algorithmic structure and realtime patch behavior can be the performance. In short, the laptop became a serious techno performance instrument. In order to document the evolution of Max/MSP/Jitter in popular culture, I compiled a series of notable live performances and projects where Max was a central part of the setup, inspiring their fans to use Max for their own music-making performances and practices. Max because a central programming language between artists who performed on the stage and in the basement, uniting an entire community around live computer music.

Video of Someone’s Algorave in Brazil

Monolake live at Ego Düsseldorf, June 5, 1999

“This is a live recording, captured at Ego club in Duesseldorf, June 5 1999. The music has been created with a self written step sequencer, the PX-18, controlling a basic sample player and effects engine, all done in Max MSP, running on a Powerbook G3. The step sequencer had some unique features, e.g. the ability to switch patterns independently in each track, which later became an important part of a certain music software” from RobertHenke.com.“Flint’s was premiered San Francisco Electronic Music Festival 2000. Created and performed on a Mac SE-30 using Max/MSP with samples prepped in Sound Designer II software. A somewhat different version of the piece appeared on the 2007 release Al-Noor on the Intone label” from “Unseen Worlds.”

The group built their shows around laptops running Max MSP, with the show being the real time processing of a system rather than fixed playback.

He used Max to create live music from Nike shoes, and generally talked about how he likes using Max MSP and Jitter to map real time physical oscillations (like grooves and needles – or the bending of shoes) into live audiovisual outcomes.

MaxMSP allows for a collective performance format, such as laptop orchestras and networked ensembles. Princeton Laptop Orchestra lists MaxMSP among the core environments used to build the meta instruments played in ensemble, turning patching into a social musical practice, not just an individual studio practice.

By highlighting MaxMSP/Jitter’s centrality within a wider canon of musicians and subcultures, and linking examples of its development through time, I hope I have demonstrated how Max has contributed to community building around live computer music. Both MaxMSP and Live Coding express the same underlying artistic proposition that the program is the performance, but it lowers the barrier for people who think in systems and signal flow rather than syntax, and it scales all the way from DIY one person rigs to commercial mixed music productions to mass user communities.

My Experience

Computers are very intimidating animals to me. Because of this, I especially appreciated Max/MSP for a couple reasons: One, because it’s so prolific within the live coding/music community, like Arduino, there is an inexhaustible well of resources to draw from to get started. For every problem or idea you have, there is a Youtube tutorial or a reddit/Cycling ’74/Facebook forum to help you out. The extensive community support and engagement makes Max extremely accessible and approachable, and promotes outreach between both beginners and serious artists. Two, Max gives immediate feedback that easily hooks and engages you.

I liked using Jitter, because visuals are just so fun. This is max patch I made some time ago, where I would feel old camcorder videos into various filters and automatically get colorful, glitchy videos.

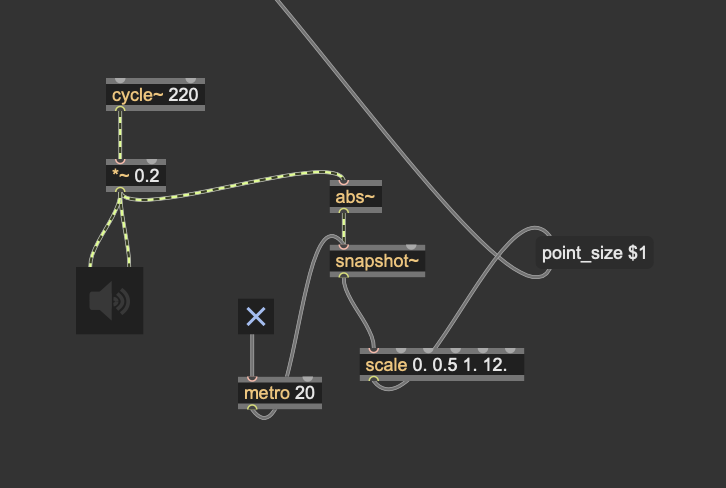

But for the purposes of this demonstration, I wanted to create a patch where visuals and sound were reacting to each other somehow. I searched up cool Max jitter patches and found a particle system box on Github, linked here: https://github.com/FedFod/Max-MSP-Jitter/blob/master/Particles_box.maxpat. Then, I searched up how I could make a basic sound that affects the size of particles, making them react to the noise realtime. I created the input object or sound (cycle), connected it to the volume (the wave cycles between those parameters, in this case -0.2 and +0.2) and the output object is the speaker, so we can hear it. In order to link this sound to the jitter patch, metro tells the transition objects to read the signal. I connected the sound signal to abs, snapshot and scale to remap it into measurements/numbers that can be read by “point-size” and visualized in jitter. Toggling the metro off stops “point size” from reading the measurements from the audio signal, severing the connection between the sound and the particles, as I demonstrate in my video. The result is, the louder the sound, the bigger the particles and vice versa. I liked using Max because it was extremely helpful to make the “physical” connections and see how an effect is created by visually seeing the signal flow, and more easily understanding how audio can be translated to visual signals in real time.

My Video

My Presentation

It also has my references/resources and links.

My Patch Code

{

"patcher": {

"fileversion": 1,

"appversion": {

"major": 8,

"minor": 6,

"revision": 0,

"architecture": "x64"

},

"classnamespace": "box",

"rect": [0.0, 0.0, 820.0, 520.0],

"bglocked": 0,

"openinpresentation": 0,

"default_fontsize": 12.0,

"default_fontface": 0,

"default_fontname": "Arial",

"gridonopen": 1,

"gridsize": [15.0, 15.0],

"gridsnaponopen": 1,

"toolbarvisible": 1,

"boxanimatetime": 200,

"imprint": 0,

"enablehscroll": 1,

"enablevscroll": 1,

"boxes": [

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-1",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "cycle~ 220",

"patching_rect": [110.0, 70.0, 80.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-2",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "*~ 0.2",

"patching_rect": [110.0, 110.0, 55.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-3",

"maxclass": "ezdac~",

"patching_rect": [90.0, 165.0, 45.0, 45.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-4",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "abs~",

"patching_rect": [310.0, 110.0, 45.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-5",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "snapshot~",

"patching_rect": [310.0, 150.0, 70.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-6",

"maxclass": "toggle",

"patching_rect": [240.0, 250.0, 24.0, 24.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-7",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "metro 20",

"patching_rect": [280.0, 250.0, 62.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-8",

"maxclass": "newobj",

"text": "scale 0. 0.5 1. 12.",

"patching_rect": [410.0, 220.0, 150.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-9",

"maxclass": "message",

"text": "point_size $1",

"patching_rect": [600.0, 220.0, 95.0, 22.0]

}

},

{

"box": {

"id": "obj-10",

"maxclass": "outlet",

"patching_rect": [725.0, 222.0, 20.0, 20.0]

}

}

],

"lines": [

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-1", 0],

"destination": ["obj-2", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-2", 0],

"destination": ["obj-3", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-2", 0],

"destination": ["obj-3", 1]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-2", 0],

"destination": ["obj-4", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-4", 0],

"destination": ["obj-5", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-6", 0],

"destination": ["obj-7", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-7", 0],

"destination": ["obj-5", 1]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-5", 0],

"destination": ["obj-8", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-8", 0],

"destination": ["obj-9", 0]

}

},

{

"patchline": {

"source": ["obj-9", 0],

"destination": ["obj-10", 0]

}

}

]

}

}