This article made me rethink how I separate art and music. I always thought of painters and bands as two different worlds, but the text shows they have been mixing for more than a hundred years. I liked the story about Paul Klee using music ideas like “fugue” in his colors, and later how punk students turned art school energy into noisy songs. It feels honest when the authors say money often decides whether someone is called an “artist” or a “musician.” That line hit me, because labels still matter today even when people switch tools on the same laptop. The piece also reminded me that raw spirit can beat perfect skill; three punk chords can share a gallery wall with video art. After reading, I feel freer to blur my own projects instead of picking one box.

Members: Jannah, Jiho, Adilbek, Clara

Adilbek and Jiho were primarily working on Hydra, and Jannah and Clara were working on Tidal code. There were a lot of improvisation sessions where we just met up and improvised whatever we wanted to do on the spot, and we felt ourselves getting more comfortable each time we did it. We also thought of how we could have an arc with a build-up, climax, and slow fade out for both visuals and our audio, and we ended up experimenting a lot with tweaking each other’s lines and building off of what the previous person wrote on Flok, etc. Overall, our sessions were sometimes unpredictable but also rewarding when there were unexpected moments of harmonization during our improv!

Link to the video: click!

This reading gave me a new way to think about what it means for music to be “live.” I never thought much about how different musicians use laptops in performance. The comparison between Deadmau5 and Derek Bailey is really interesting. Deadmau5’s shows are big, flashy, and mostly pre-recorded, while Bailey’s performances are improvised and unpredictable. Live coding seems to sit in the middle. It uses computers, but in a way that’s more like playing an instrument in real time.

I liked how the authors talked about the audience being able to see the code on the screen. It is a cool way of showing that something real is happening, even if it’s not physical like playing guitar. It also made me think about how we value “work” in music, sometimes we want to see someone sweating on stage to believe they are doing something real. Overall, I found this piece a bit long and academic, but the core idea of rethinking what counts as live performance is really stuck with me.

Hydra Code:

let p5 = new P5();

p5.createCanvas(p5.windowWidth - 100, p5.windowHeight - 100, p5.WEBGL, p5.canvas);

s0.init({src: p5.canvas});

src(s0).out();

p5.hide();

p5.angleMode(p5.DEGREES);

p5.colorMode(p5.HSB);

p5.stroke(199, 80, 88);

p5.strokeWeight(3);

p5.noFill();

p5.pixelDensity(1);

let r = p5.width / 3;

let rotationSpeed = 0.8;

let hueShift = 0;

const settings = [0.75, 5, 5];

p5.draw = () => {

p5.clear();

p5.orbitControl();

p5.rotateX(p5.frameCount * rotationSpeed);

p5.rotateY(p5.frameCount * rotationSpeed);

settings[0] = cc[0] || 0.75;

settings[1] = cc[1] ? cc[1] * 10 : 5;

settings[2] = cc[2] ? cc[2] * 10 : 5;

p5.rotateX(65);

p5.beginShape(p5.POINTS);

for (let theta = 0; theta < 180; theta += 2) {

for (let phy = 0; phy < 360; phy += 2) {

let x = r * (1 + settings[0] * p5.sin(settings[1] * theta) * p5.sin(settings[2] * phy))

* p5.sin(theta) * p5.cos(phy);

let y = r * (1 + settings[0] * p5.sin(settings[1] * theta) * p5.sin(settings[2] * phy))

* p5.sin(theta) * p5.sin(phy);

let z = r * (1 + settings[0] * p5.sin(settings[1] * theta) * p5.sin(settings[2] * phy))

* p5.cos(theta);

p5.stroke((hueShift + theta + phy) % 360, 80, 88);

p5.vertex(x, y, z);

}

}

p5.endShape();

hueShift += 0.1;

}

src(s0)

.modulatePixelate(noise(()=>cc[2]*20,()=>cc[0]),20)

.out()

src(s0).modulate(noise(4, 1.5), 0.6).mult(osc(1, 10, 1)).out(o2)

render(o2)

src(o2)

.modulate(src(o1).add(solid(0, 0), -0.5), 0.005)

.blend(src(o0).add(o0).add(o0).add(o0), 0.1)

.out(o2)

render(o2)

hush()

TidalCycle Code:

d1 $ ccv "0 40 80 127" # ccn "0" # s "midi"

d2 $ slow 4 $ rotL 1 $ every 4 (# ccv (fast 2 (range 127 0 saw))) $ ccv (segment 128 (range 127 0 saw)) # ccn "1" # s "midi"

d3 $ slow 4 $ ccv (segment 128 (slow 4 (range 127 0 saw))) # ccn "2" # s "midi"

d4 $ slow 4 $ note "c'maj d'min a'min g'maj" # s "superpiano" # legato 1 # sustain 1.5

d5 $ slow 4 $ note "c3*4 d4*4 a3*8 g3*4" # s "superhammond:5"

# legato 0.5

xfade 4 $ "bd <hh hh*2 hh*4> sd <hh [hh bd]>"

# room 0.2

once $ s "auto:3"

hushLink to the video.

My project draws inspiration from the tragic beauty of human ambition and its inevitable unraveling. It mirrors the story of Itachi Uchiha and the Akatsuki—a tale of sacrifice, idealism, and the fragile line between unity and destruction.

The first act symbolizes Itachi’s life: a solitary figure burdened by impossible choices. Like a bird caged by duty, he sacrificed his own peace to protect others, yet became a villain in the eyes of those he loved. This duality—the hidden cost of “greater good”—fuels the emotional core of the piece.

The second act shifts to Akatsuki’s founding philosophy: a desperate belief that peace could be forced through control. Their vision wasn’t born from cruelty but from the scars of war—a distorted hope that unity might emerge if humanity was stripped of free will. It’s a reflection of how trauma can twist even noble intentions into something monstrous.

The third act honors the group’s origins—three orphans who dreamed of healing a broken world. Their early bonds were pure, a fragile alliance against suffering. But as power grew, so did divisions. Greed, ego, and conflicting ideologies poisoned their unity, mirroring how movements often lose their way when scale replaces purpose.

The final collapse isn’t just about failure—it’s a warning. Societies built on suppression, even with grand ideals, crumble when empathy dies.

Live Demo

TidalCycle Code

do

d1 $ ccv "0 20 64 127" # ccn "0" # s "midi"

d2 $ rotL 1 $ every 4 (# ccv (fast 2 (range 127 0 saw))) $ ccv (segment 128 (range 127 0 saw)) # ccn "1" # s "midi"

d3 $ ccv (segment 128 (slow 4 (range 127 0 saw))) # ccn "2" # s "midi"

d10 $ ccv "10 40 80 127" # ccn "3" # s "midi"

hush

d11 $ s "birds:3" # gain 0.5

d4 $ slow 4 $ note "c'maj d'min a'min g'maj" # s "superpiano"

# legato 1

# djf 0.3

# gain 0.85

# sustain 1.75

d11 silence

d5 $ slow 4 $ note "c3*4 d4*4 a3*8 g3*4" # s "superhammond:5"

# legato 0.5

xfade 4 $ "bd <hh hh*2 hh*4> sd <hh [hh bd]>"

# room 0.2

d6 $ s "~ cp" # gain 1

once $ s "auto:3"

d7 $ jux rev $ slow 4 $ arp "up down diverge converge" $ note "c'maj'4*2 d'min'4*2 a4'min'4*2 g4'maj'4*2" # s "supervibe"

d8 $ hurry 2 $ s "bd hh sd hh"

do {

d6 silence;

d8 silence;

d1 $ qtrigger $ filterWhen (>=0) $ seqP [

(0,1, s "[bd*2] [hh cp]"),

(1,2, s "[bd*4] [hh cp]")

] # gain (slow 4 (range 0.8 1 saw));

once $ s "auto:3";

d5 $ qtrigger $ filterWhen (>=0) $ seqP [

(0, 1, s "~ cp"),

(1, 2, s "~ cp*2")

] # speed (slow 4 $ range 0.5 2 tri)

# pan (slow 8 $ sine);

d3 $ qtrigger $ filterWhen (>=0) $ seqP [

(0, 2, s "hh*8")

] # gain (slow 4 $ range 0.7 1.2 saw);

d4 $ qtrigger $ filterWhen (>=0) $ seqP [

(0, 1, s "~ arpy"),

(1, 2, s "arpy(3,8)"),

(2, 3, s "arpy(5,8)"),

(3, 4, s "arpy(8,8)"),

(4, 5, fast 0.5 $ s "superhoover" >| note (arp "updown" (scale "minor" ("<5,2,4,6>"+"[0 0 2 5]") + "c4")) # room 0.3)

] # note (scale "minor" $ run 8)

# cutoff (slow 4 $ range 300 3000 sine)

# resonance 0.2 # gain 1.2;

hush

}Hydra Code

s0.initVideo("birds.mp4")

src(s0)

.thresh(0.3, 0.04)

.invert()

.blend(solid(0, 0, 0), () => {

// Calculate the fade amount based on video progress

const video = s0.src

const fadeStartTime = video.duration - 5 // Start fading 5 seconds before the end

const fadeAmount = Math.max(0, (video.currentTime - fadeStartTime) / 5)

return fadeAmount

})

.rotate(() => Math.sin(time))

.out()

osc(40,-0.01,1)

.modulate(voronoi(3))

.contrast(1)

.kaleid(360)

.mask(shape(40, .6).scale(1,1))

.out(o0)

src(o0)

.rotate(1.57, 0.2)

.modulate(noise(() => cc[3] * 40, 0.1))

.add(src(o0), () => 0.01 + cc[1])

.scale(1 + .5, .7).saturate(-0.5)

.scale(() => 1 + Math.sin(time / 15) * 0.2)

.saturate(0.1)

.rotate(0,-0.1)

.out(o1)

render(o1)

voronoi(10,1,5)

.brightness(()=>Math.random()*0.15)

.modulatePixelate(noise(()=>cc[2]*20,()=>cc[0]),100)

.out()

voronoi(10,1,5).brightness(()=>Math.random()*0.15)

.modulatePixelate(noise(()=>cc[2]*20,()=>cc[0]),100)

.color(()=>0,5,3.4).contrast(1.4)

.add(shape(7),[cc[0],cc[1]*0.25,0.5,0.75,1])

.out(o0)

voronoi(10,1,5).brightness(()=>Math.random()*0.15)

.modulatePixelate(noise(cc[0]+cc[1],0.5),100)

.color(()=>0,0.5,0.4).contrast(1.4)

.out(o0)

hush()

Ryoichi Kurokawa’s work is fascinating because it combines art, science, and technology in such a unique way. I was struck by how he takes something as vast as the universe or as small as a butterfly’s wing and transforms it into abstract sounds and visuals. His attention to detail, like using NASA data or recording waterfalls in Iceland, shows his dedication to capturing the essence of nature.

I also found it interesting how Kurokawa views his work as “time design.” His ability to create immersive experiences, whether through live performances or installations like Octfalls, makes his art feel alive and dynamic. The balance between chaos and order in his pieces reflects the natural world beautifully.

What stood out most was his use of synaesthesia—not literally but conceptually—to connect senses and emotions. It’s inspiring how he bridges science and creativity to reveal the hidden beauty of the world around us. Kurokawa’s work feels like an invitation to look closer at both the grand and the microscopic.

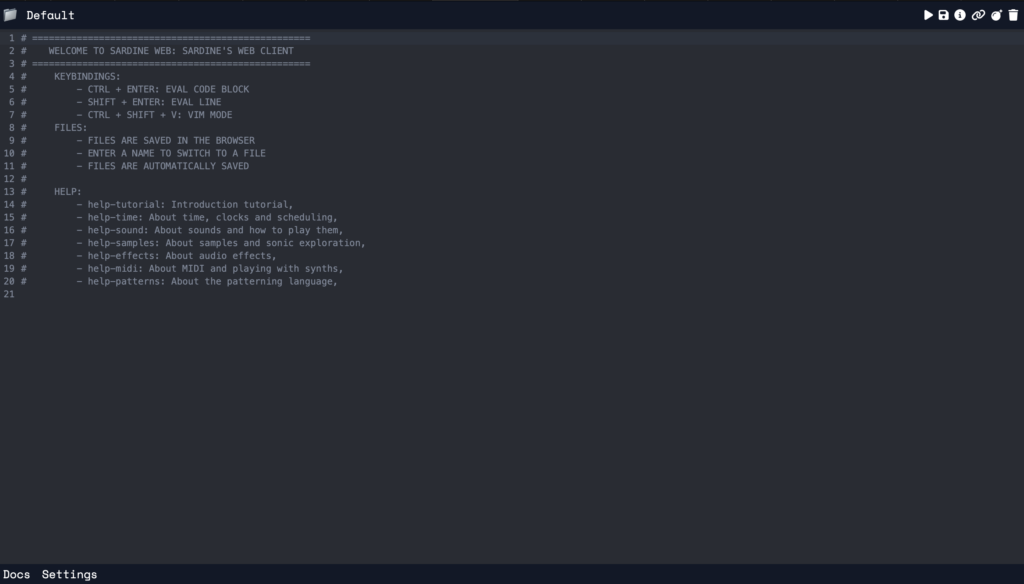

What is Sardine?

For my research project, I chose the live coding platform Sardine. I decided to go with Sardine because it stands out as a relatively new and exciting option built with Python. Sardine is a live coding environment and library for Python 3.10 and above. What sets Sardine apart is its focus on modularity and extensibility. Key components like clocks, parsers, and handlers are designed to be easily customized and extended. Think of it as a toolkit that allows you to build your own personalized live coding setup. It allows the customisation of IO logic, without the need to rewrite or refactor low-level system behaviour.

In its complete form, Sardine is designed to be a flexible toolkit for building custom live coding environments. The core components of Sardine are:

- A Scheduling System: Based on asynchronous and recursive function calls.

- A Modular Handler System: Allowing the addition/removal of various inputs/outputs (e.g., OSC, MIDI).

- A Pattern Language: A general-purpose, number-based algorithmic pattern language.

- For example, a simple pattern might look like this:

D('bd sn hh cp', i=i)

- For example, a simple pattern might look like this:

- The FishBowl: A central environment for communication and synchronization between components.

However, configuring and using the full Sardine environment can be complex. This is where Sardine Web comes in. Sardine Web is a web-based text editor and interface built to provide a user-friendly entry point into the Sardine ecosystem. It simplifies the process of writing, running, and interacting with Sardine code.

The Creator: Raphaël Maurice Forment

Sardine was created by Raphaël Maurice Forment, a musician and live-coder from France, based in Lyon and Paris. Raphaël is not a traditional programmer but has developed his skills through self-study, embracing programming as a craft practice. He is currently pursuing his PhD at the Jean Monnet University of Saint-Etienne, focusing on live coding practices. His work involves building musical systems for improvisation, and he actively participates in concerts, workshops, and teaching live coding both in academic and informal settings.

Sardine began as a side project to demonstrate techniques for his PhD dissertation, reflecting his interest in exploring new ways to integrate programming with musical performance. Raphaël’s background in music and his passion for live coding have driven the development of Sardine, aiming to create a flexible tool that can be adapted to various artistic needs.

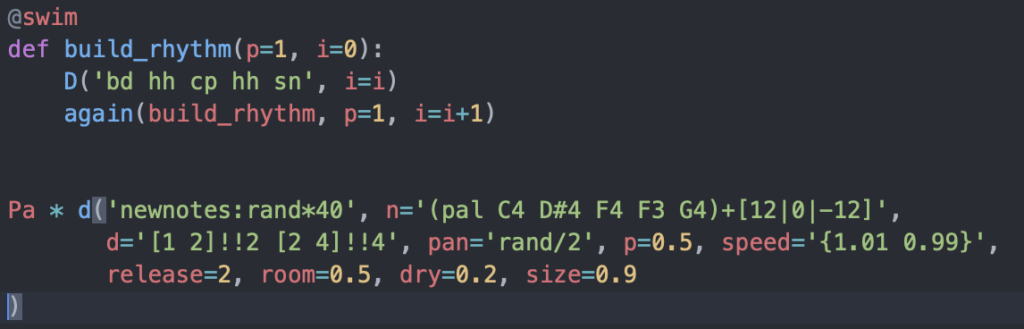

My Live Demo

To demonstrate Sardine in action, I created a simple piece that highlights its scheduling and pattern language capabilities.

In this code snippet I used two different types of senders (d for Player and D for swim) where Player used for shorthand pattern creation, and @swim used for fundamental mechanism to create patterns.

Sardine in the Context of Live Coding

Sardine builds upon the ideas of existing Python-based live coding libraries like FoxDot and TidalVortex. However, it emphasizes flexibility and encourages users to create their own unique coding styles and interfaces. It tries to avoid enforcing specific ‘idiomatic patterns’ of usage, pushing users to experiment with different approaches to live performance and algorithmic music.

The creators of Sardine were also inspired by the Cookie Collective, a group known for complex multimedia performances using custom setups. This inspired the idea of a modular interface that could be customized and used for jam-ready synchronization. By allowing users to define their own workflows and interfaces, Sardine fosters a culture of experimentation and innovation within the live coding community.